|

The name of the turtle in Egyptian was Shetyw, Shetw,

Sheta (Worterbüch IV, 557).

Sheta was also the Tortoise constellation (Turtles pair) and then one

of the 36 decans.

Turtle remains have been found in archaeological deposits since epipaleolithic

and Khartoum Mesolithic (Midant-Reynes, Prehistoire, 83, 93, 97) as

also at Merimde (Vandier, Manuel, I, 123, 165; Boessneck, Die Tierwelt, 111), Maadi and El-Omari.

Some bracelets and rings from turtle carapace scales are known in the

Badarian period (ibid., 213f.).

Large amounts of turtle bones have been found in the important ceremonial

complex at Hierakonpolis loc. 29A.

[There is also a unique representation in a graffito from the Eastern Sahara rock art (Karkur Talh, Gebel Uweinat): the fresh water (?) turtle is reproduced head-up, is c. 70cm long from the tail to the poorly preserved head (which seems somewhat rounded rather than sharply pointed), with the triangular sharp tail visible below out of the carapace (nearly extending as long as the paws); on the left of the reptile two girafes à lien are carved; this could also be a land tortoise (see the photo and link in the bibliography below)].

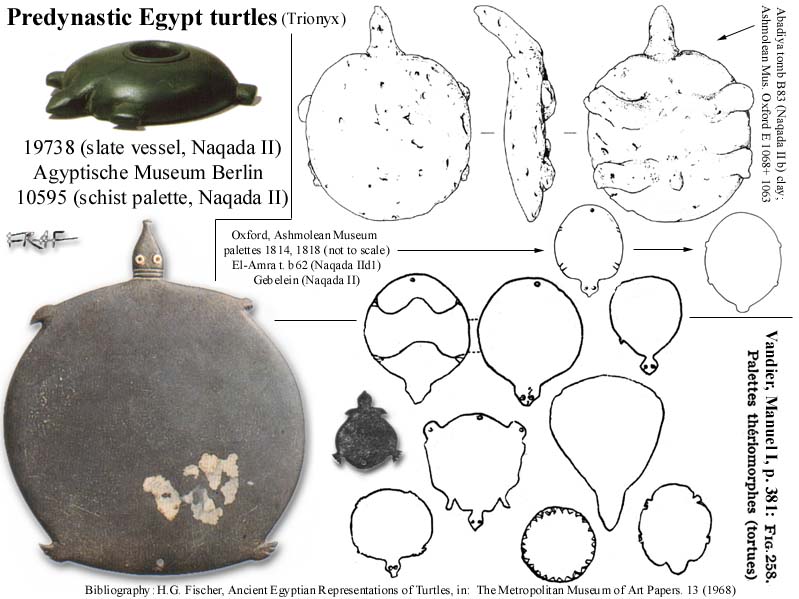

Many predynastic slate palettes

represent freshwater (soft carapace, Trionyx triunguis) turtles as does

the later hieroglyph for "turtle" (Gardiner's sign list I2; Budge, Dict.,

List IX, 1-2), in which the chelonian is always represented as seen

from above. These kind of zoomorphic palettes are found since the Amratian

but especially in Gerzean (Naqada II) period (Vandier, op. cit., 381,

443, 459; Cialowicz, Les Palettes, 35-37); in this phase also the earliest

zoomorphic stone-vessels begin to be produced (see the one in Berlin

Mus. 19738 in the figure) as well as pottery (P-class, cf. Abusir el-Meleq

fragment in: Vandier, op. cit., 452, fig. 301, n. 73); both these vessel

types in the shape of turtles are however far less frequent than palettes.

Naqada III and Early Dynastic turtle-shaped palettes are rarer and very

stylized artifacts in which the original features of the animal are

always hard to recognize (ibid., 808), being often degenerated to pure

ovals or circles.

Baumgartel (Cultures, 1960, 84) states that the most realistic examples

date late Naqada I; Cialowicz (1991, 35f.) stresses the superior popularity

that this type shared during Naqada II.

A turtle is depicted on a famous C-ware (Naqada I) cup (Vandier, op. cit., fig.

184; Petrie, Preh. Eg., 1920, pl. 23.2), but this is almost an unicum

and there's no corresponding attestation in the subsequent Naqada II

decorated (D) pottery.

The famous Hunters

palette shows most of the hunters on the right side (the photo in fig. 2 is turned 90° CCW) carrying a kind of shield which Keimer

(BIE 32, 1950, 76-94; Vandier, op.cit., 576) interpreted as a turtle-carapace

shield (or also as a coiled rope, which is in my opinion very unprobable at a close examination).

But the object has also a close resemblance to a type of palette

(cf. Petrie-Quibell, Naqada and Ballas,1896, pl. 48, nr. 60, 61, 59).

Given the (ritual -) hunting context of the Hunters palette, an identification

of those objects as palettes (which must have had an important magic

role in "cynegetic" symbolism and practices owing to their

use in grinding eye and body paint) makes more sense than the interpretation

as shields (which instead would be useful in warfare not certainly in

hunting, even the big game one). It also seems that a shield of that size would be scarcely useful.

However Keimer cited modern parallel

(op. cit., fig. 14-18) of Nile river and Red Sea turtles shields used

among Sudanese tribes as Bishari and Abadi.

For shields also cf. A. Nibbi, Some Remarks on the Ancient Egyptian Shield, in: ZAS 130, 2003, 170-181.

An unprovenanced alabaster vessel from a private collection (Kaplony,

Steingefasse, 1968, 13f., nr. 2, note 23; pl. 1, 12, 14) is decorated

with a relief consisting of a crocodile, a scorpion, a turtle, another

scorpion and another crocodile (C-S-T-S-C).

Turtles are notably absent from the repertoires of votive objects (mainly

faience and pottery) found in the temples caches at Elephantine, Hierakonpolis,

Abydos and Tell Ibrahim Awad. There are only few known predynastic figurines representing chelonians. Turtles are notably absent from the repertoires of votive objects (mainly

faience and pottery) found in the temples caches at Elephantine, Hierakonpolis,

Abydos and Tell Ibrahim Awad. There are only few known predynastic figurines representing chelonians.

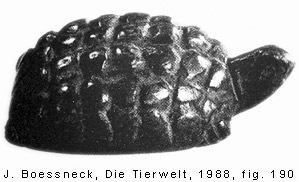

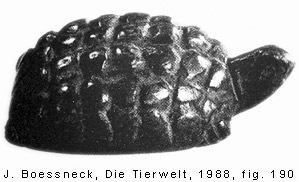

A small steatite figurine (length 5,8 cm) of land turtle is published by A.P. Kozloff, (in: Tierbilder aus vier Jahrtausenden. Antiken Sammlung Mildenberg, 1983, nr. 45) and reported by J. Boessneck (Die Tierwelt, 1988, 111, fig. 190). See fig. 3 >

Another very rare find-type is the Ashmolean Museum (cf. reference in fig. 1 above) clay tortoise from Abadiya

tomb B83 (early Naqada II).

Perhaps a further exception might be the flint in Petrie's Preh. Eg. (1920) pl.

VII,9 (= UC

15172), which is by no means surely a turtle [cf. S. Hendrickx,

D. Huyge, B. Adams, Le scorpion en silex du Musée royal de Mariemont,

in: Cahiers de Mariemont, suppl. to n. 28-29 (1997/1998), 2003, p. 14,

n. 48, p. 16].

The hieroglyph (Gardiner I2) is not attested in the Early Dynastic period

(no entry in Kahl's corpus).

To my knowledge neither the O.K. Pyramid Texts ever mention turtles

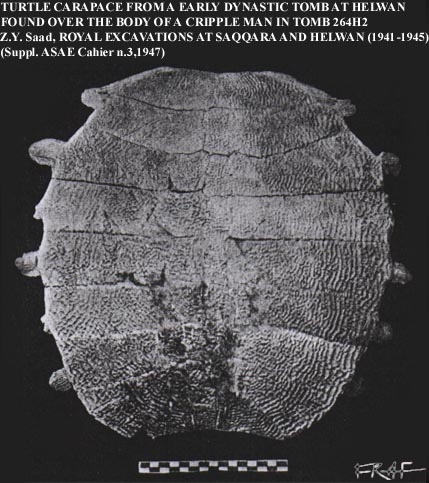

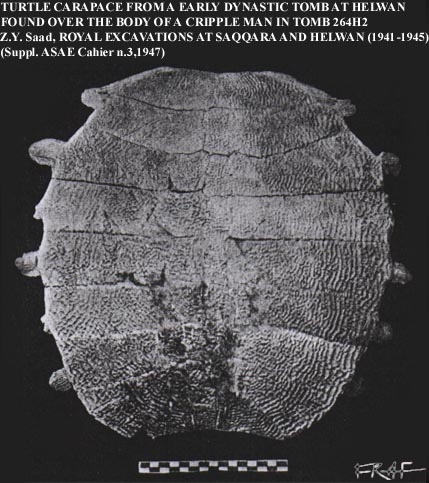

or turtle-fiends. An astonishing use was made of a land-turtle carapace

in an Early Dynastic tomb at Helwan (tomb

264H2, small oval cut in the gravel, m 1,2x0,8 x0,9 deep): the tomb

owner had lost his feet (and the legs from c. 12 cm below the knees)

in some accident and he had been buried (in contracted position, head

to the east and face to the north) beneath the carapace. Zaki Saad thought

that the animal had to symbolize the "way in which the owner

used to move about crawling on his hands and knees and thus going slowly

like a tortoise". I think that a turtle carapace might have

been, for a cripple man, a very useful means to move sitting within

it and proceeding in the manner suggested by Saad. But no further similar

occurrance and use of turtle skeletons is known in Egypt, and I don't

know about any mythical, religious or cultual connections between cripple

men and turtles (photo in fig. 4, below).

Turtles are (alike pork) notably missing in E.D. and Old Kingdom offering

tables/lists and person names (cf. Kaplony, KBIAF, 1966, 32) with very

few exceptions: Junker, Giza VIII, 117; XI, 124; a possible person name

Njj(t)-Stw [shetw] on Cairo CG 1616; Mond-Myers, Armant I, 254f.; Reisner,

Naga ed-der III, 158.

For representations of Nile turtle under a boat in O.K. tomb of Mehu,

Saqqara, cf. Keimer, op. cit., fig. 21.

In Middle Kingdom ivories with carved or incised animals (among which

also some turtles) are known from various museums (Cf. Altenmuller,

Apotropaia; EEF archive), these having magical-apotropaic functions

(see D. J. Osborn - J. Osbornovà, The Mammals of Ancient Egypt,

1998, 7-8, fig. 1.14d).

Also various implements were built with turtle plates as combs, bracelets,

knife hilts and amulets, but these objects were probably from Red

Sea turtles, Chelonia Imbricata (Fischer, in: L.Ä V). According to Fischer, marine turtles are nearly absent from Egyptian representations, which show soft shell turtles 'almost without exception".

Apart from the mentioned exceptions, no king, god or further personal

names are known to me which include the turtle/tortoise determinative

or name.

There is however a turtle-headed guardian demon (resin coated wood)

in the (King Valley 57) tomb of Horemheb (E. Russmann, 2001, 160f.).

A (land-)tortoise headed deity (or apotropaic figurine?) was found by

G. Belzoni in the tomb of Ramses I (K.V. 16) in early October 1817 (N.

Reeves-R.H. Wilkinson, The Complete Valley of the Kings, 1996, 134-5,

second fig. below from left); it was carved in sycamore wood and the statuette represented

a human figure sitting on the ground; over the neck and the lower part

of the wig there was a large horizontal tortoise modeled without legs

and with the head out. The name and function of this deity is not known

but it might be (related to) the Decan Sheta.

An evil god (an enemy of the sun-god Ra, like Apophis and the Hippopotamus)

is mentioned in Book of the Dead chapters 4, 83, 161; anyhow turtles

have not the same relevant role in Ancient Egyptian symbolism, iconography

and myths as they do e.g. in Hinduism or in Mesoamerican myths (but

cf. Keimer, op. cit., 94).

Since the XIXth Dynasty and particularly in the Late and Greco-Roman

periods, turtles are known to have been ritually speared by kings and

nobles with the harpoon, as is the case of the Theban tomb (157) of

Nebunenef (cf. Säve-Soderbergh, 1956, fig. 1). The text above the

depiction runs: "Töten der Schildkröte des (od. für)

Rê von Osiris, dem Hohenpriest des Amun, Nebunenef. Er sagt: Es

lebe Rê, es sterbe die Schildkröte. Unversehrt ist derjenige

im Sarge".

The Ebers Medical papyrus (57,6; 86,12) cites some employ of turtles

(carapace and organs) in certain formulas.

For a representation of a Nile turtle in a M.K. tomb of Meir cf. Keimer,

op. cit., fig. 22.

Turtles are among the tributes represented in the relief of Punt of

the Hatshepswt temple at Deir el-Bahari (trionyx).

Apart from the mentioned (possible) shield carried by men on the Hunters

palette and the implements listed above, no other practical use is known

of soft shell turtles (but see Keimer, op. cit., 76ff., fig. 13b); but

land tortoise carapaces (Testudo Kleinmanni) were used as sounding-board

for lutes and as a bowl...

... The flesh of Trionyx was eaten from Predynastic times and as late

as the Old Kingdom (L.Ä.); later (as it appears since the Coffin

Text) the flesh of turtles began to be considered "abomination

of Ra", and contemporarily the role of these animals became an

evilish one (see above; for lutes see Vandier, Manuel IV, 1964, 377f.).

Also Lucas - Harris (1962, p. 39) mention the use of turtle "shells"

as part of rings, bracelets, or dishes, combs and also as sounding board

of an harp and of a mandolin.

GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHY

Henry G. Fischer, Ancient Egyptian Representations

of Turtles (MMA papers 13, New York, 1968).

id., Schildkröte, LÄ V, 627-628.

B. van de Walle, La tortue dans la religion et la magie égyptiennes,

in: La nouvelle Clio 5, 1953, 173-189.

J. Boessneck, Die Tierwelt des Alten Ägypten, 1988, 24, 110-112,

fig. 184-190.

For Predynastic/Naqada I:

C. Wolterman, C-ware Cairo Dish CG 2076 and D-ware flamingos: prehistoric

theriomorphic allusions to solar myth, in: JEOL 37, 2002, 5-30.

Middle Kingdom:

H. Altenmueller, Die Apotropaia und die Goetter Mittelaegyptens, Part

I, p.139 (München, 1965).

New Kingdom:

T. Säve-Soderbergh, Eine ramessidische Darstellung vom Töten

der Schildkröte, in: MDAIK 14, 1956, 175-180.

For religious aspects of turtles at the Graeco-Roman period:

A. Gutbub, "La tortue animal cosmique et bénéfique à l'époque ptolémaïque

et romaine", in: Hommages Sauneron (BdE 87) vol. I, 391-435 (thanks

to J. D. Degreef).

Role of turtles in ancient Egyptian religion also cf. Kees, Gotterglaube,

1941, 63f., 69-70; P. Vernus, The Gods of Ancient Egypt, p. 155 (London-New

York, 1998); see also the entry in the Lexicon cit. above and the EEF

link below.

HELWAN tomb 264H2:

Z.Y. Saad, Royal Excavations at Saqqara and Helwan (1941-1945), Suppl.

ASAE Cahier n.3, 1947, 108-9, fig. 9, pl. 47.

PALETTES:

W.M.F. Petrie, Prehistoric Egypt (London, 1920).

id., Corpus of Prehistoric Pottery and Palettes (London, 1921).

W.M.F. Petrie, H. Petrie, M.A. Murray, Ceremonial Slate Palettes (London,

1953).

W. Needler, Predynastic and Archaic objects in the Brooklyn Museum,

1984, p. 323-324 (Cat. 256, Brooklyn Mus. 07.447.619); plate 58.

J. Crowfoot-Payne, Catalogue of the Predynastic Egyptian Collection in the Ashmolean Museum. Oxford 1993.

11 palettes, p. 222-223 (cat. 1809-1819), fig. 75; clay figurine (cat. nr. 68 = E1068+1063), p. 22, pl. 15 (nr. 68).

K.M. Cialowicz, Les Palettes Egyptiennes aux motifs zoomprphes et sans décoration (Krakòw, 1991).

(See also the bibliography to the page of Palettes

in this website). SHIELDS:

L. Keimer, in: BIE 32, 1950, 49-101 (note 3: p. 76-95, fig. 13-23; many

ethnographical notes on modern Sudanes tribes)

A. Lucas - J.R. Harris, Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries (4th

ed.) 1962, 39

A. Nibbi, Some Remarks on the Ancient Egyptian Shield, in: ZAS 130, 2003, 170-181.

HOREMHEB KV57 tomb, turtle-headed demon: Edna R.Russmann (ed.), Eternal

Egypt, Masterworks of Ancient Art from the British Museum, page 160-161,

Nr.72 (London, 2001). [Thanks to Bastiaan Lieffering for pointing me

out this reference].

ON-LINE

-EEF

forum discussion on Turtle magical-ivories: November 1998 zip-archive.

- For a unique representation of turtle (Trionyx Tr., Geochelone Sulcata or Testudo Kleinmanii ?) in Eastern Sahara rock art (Karkur Talh) see HERE this picture (Thanks to G. Negro for informing me about it)

- Andras Zboray, Rock Art of the Libyan Desert, Newbury, 2005 (DVD).

MARINE TURTLES in various past cultures (does not include Egypt/Africa):

Jack Frazier, Marine Turtles of the Past: a Vision for the Future?

in: R.C.G.M. Lauwerier, I. Plug (eds.), The Future from the Past. Archaeozoology in wildlife conservation and heritage management, 2004, 103-116 (chapter 10)

(Proceedings of the 9th Conference of the International Council of Archaeozoology, Durham 2002) |

Turtles are notably absent from the repertoires of votive objects (mainly

faience and pottery) found in the temples caches at Elephantine, Hierakonpolis,

Abydos and Tell Ibrahim Awad. There are only few known predynastic figurines representing chelonians.

Turtles are notably absent from the repertoires of votive objects (mainly

faience and pottery) found in the temples caches at Elephantine, Hierakonpolis,

Abydos and Tell Ibrahim Awad. There are only few known predynastic figurines representing chelonians.